How to Start Improvising on Fiddle Tunes

Confession time.

I’ve always been nervous about improvising solos. If you’ve been in a band with me or perhaps been a particularly observant audience member, you know that I usually pass on the opportunity to step up to the mic and bust out a dazzling solo. I much prefer creating a backup to weave in and out of the soloist, supporting and pushing/following them on to their destination- it’s when I feel the most creative- on stage, but out of the spotlight.

Something shifted when I had kids. (Well, MOST things changed, but let’s stay focused). I realized that while I’m parenting, I’m improvising everything. Literally. How will I get him to sleep? To eat? Once you find a method that works, the next day, the kid changes it up on you. Back to improvising. And, my son wanted me to sing all.the.time, so I’d make up melodies or write new lyrics or find a rhythm to accompany our task at hand. Opportunities to practice were so rare that when I played my fiddle for myself (as opposed to teaching), I developed a new mentality: just wing it. Go for it. Play, no matter what. I started to improvise around melodies and not just chordally. I was slowly becoming more comfortable with the uncomfortable unknown.

I am an interesting candidate for writing this post. Improvising is something I am still forcing myself to practice. But sometimes the people who have to really work through something end up being good at explaining their process. I learned this when Laura Risk was going over chords for a tune she taught at Alasdair Fraser’s Valley of the Moon Scottish Fiddling School. Laura mentioned this very idea- she said something along the lines of, ‘chords don’t always come easily to me, but I can explain them in a way that will hopefully help you realize you can try them too.’ And she was so great! (Not surprising if you’re at all familiar with Laura.) At the time, I was already pretty comfortable with chords, but during that lesson, she showed me the function of a flat seven-chord in Mixolydian and minor tunes*. Thank you, Laura!

So with this in mind, here are some gentle ideas of how to get started improvising on your fiddle tunes. (By the way- these concepts aren’t specific to the fiddle- all the instruments can apply these techniques.)

Find the Bones

The ‘Bones’ are the essential notes of the melody. Often these notes happen on the beats, and the connective tissue aka notes between the bones are negotiable. That’s why there can be so many versions of the same fiddle tune. If ten different fiddlers played the melody to ‘Soldier’s Joy’, all ten versions would be identifiable yet slightly different. Being able to pinpoint the similarities and differences between versions is a helpful way to start offering your own version of the tune and beginning to improvise.

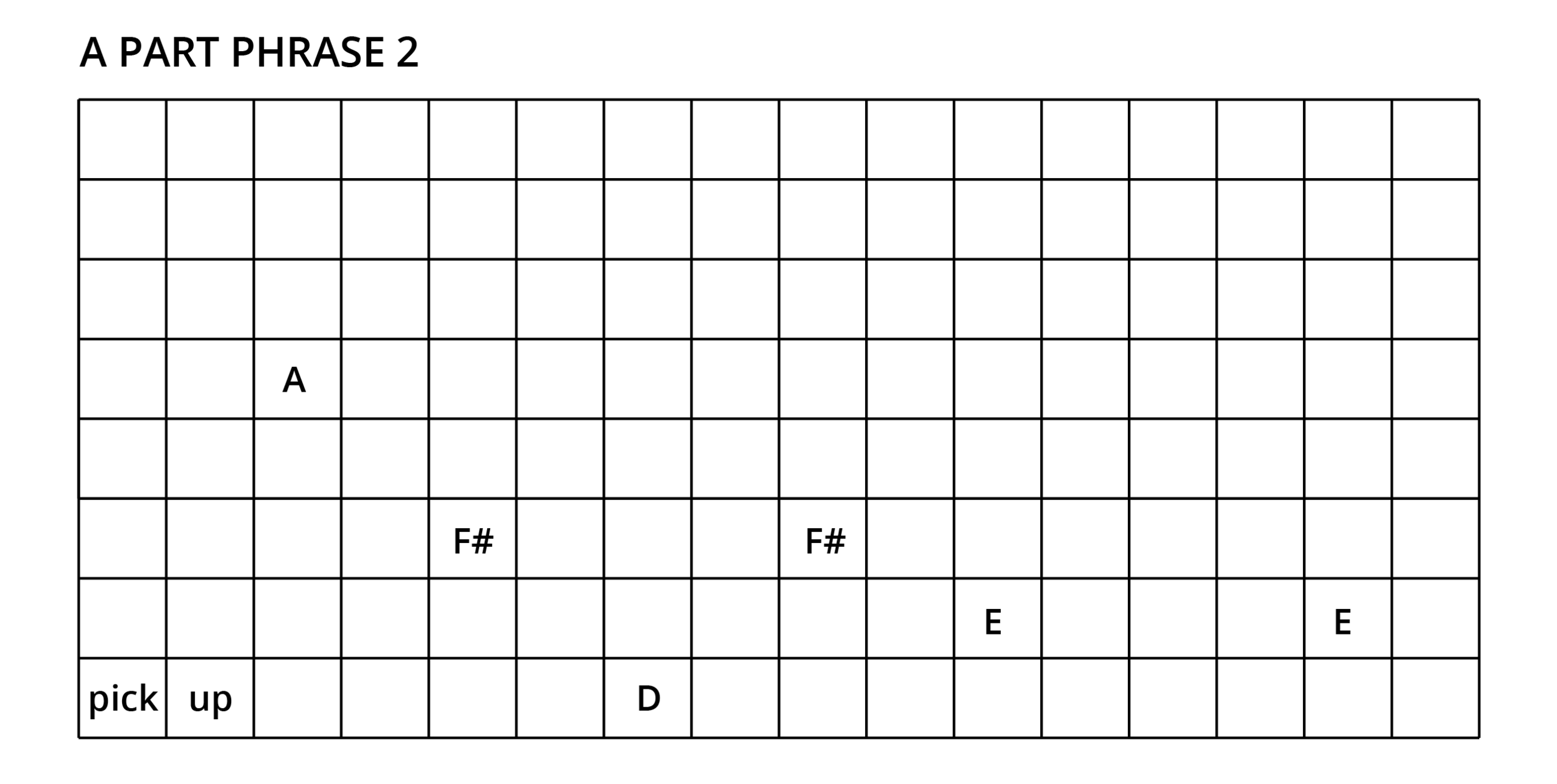

Here are the ‘bones’ of Soldier’s Joy. You could even strip the F#s away from the first three phrases if you want extreme minimalism!

Start small, with pickups

“Pickups” are the notes that point everyone to the downbeat, aka the first beat. They serve an important rhythmic purpose in dance music- they literally tell the dancers when to pick up their feet so they can then put them down on the down beat. Without a pickup, there’s no prep- your feet are already on the floor! They also provide melodic and harmonic information by leading us to our chordal destination. Pick ups often take place during beat 4, but can stretch out and use more beats/space. Melodically, they help connect one phrase to another by approaching from above or below.

You could start to improvise by changing your pickup choices at every opportunity- keep the rest of the tune as is (the bones!): just change what you’re doing with your pickups. You’ll first need to

Figure out what your landing note is (ie the downbeat) for each phrase.

Discover pickups. Approach your landing note with one note from above. Approach your landing note with one note from below. Then approach with two notes, then three. Keep track of your rhythm, bowing, or picking pattern.

Practice playing every opportunity with each pickup choice. It’s time-consuming and not necessarily the most musical, but you’ll want to strengthen your vocabulary for when it comes time to….

Go for it! That means choose your pickups! Aka improvise. Play a different possibility every time.

Here are 18 Options for Pickups approaching an A note. I’m still using the tune Soldier’s Joy as a reference. (Key of D).

One note from above: D or B. You could play either a full quarter note or just an eighth note.

Two notes from above: DB, or C#B. These notes would be eighth notes, two notes fill the entire 4th beat.

Three notes from above: DC#B. These notes could either be eighth note triplets which would fill the entire 4th beat, or three eighth notes, which would use half of beat three and the entire 4th beat.

Old time! Use the downbeat pitch as a pickup. In this case, it’s an A, so start playing the A on beat 4 and carry it over the barline into beat 1.

One note from below: G or F#. You could play either a full quarter note or just an eighth note.

Two notes from below: F#G. These notes would be eighth notes, two notes fill the entire 4th beat.

Three notes from below: F#GG#, or EF#G. These notes could either be eighth note triplets which would fill the entire 4th beat, or three eighth notes, which would use half of beat three and the entire 4th beat.

Here’s a video of me demonstrating the above ideas.

Add Some Meat

Now that you’re getting better at making choices on the spot, there are lots of formulaic ways to go about adding ideas to the bones. Here are some tried and true methods you’ll most likely recognize the sound of when you try them out.

Arpeggios and Thirds

Arpeggios/thirds outline the chord and feel familiar in your hands. Here’s an example of adding them to a few phrases in Soldier’s Joy:

Or even more arpeggios to the same phrase:

Passing Tones

An incredibly ubiquitous filler is to play scales! Connect the bones by passing through adjacent notes. This technique is often referred to as using ‘passing tones’. Here’s an example: (The ‘bones’ are bold).

Permutations

An infinite way to systematically improvise is by practicing different permutations of notes. I’m referring to four note melodic groupings- the numbers referring to scale degrees. If you apply the permutation(s) to the bones of the tune, you can combine them in curious and interesting ways. I picked up this idea through Matt Glaser’s Bluegrass Fiddle and Beyond Book. He introduced the idea on Blackberry Blossom and it’s quite the workout! I’ve been trying to implement it in other tunes.

Here are six combinations of permutations for the fourth phrase.

In the first set uses the F# as the 1 and the second set uses the E as the 1.

1231 1231 = F#GAF# EF#GE

3213 3212 = AGF#A GF#EF#

3213 1231 = AGF#A EF#GE

1231 3216 = F#GAF# GF#EC#

3123 3216 = AF#GA GF#EC#

1321 3161 = F#AGF# GEC#E

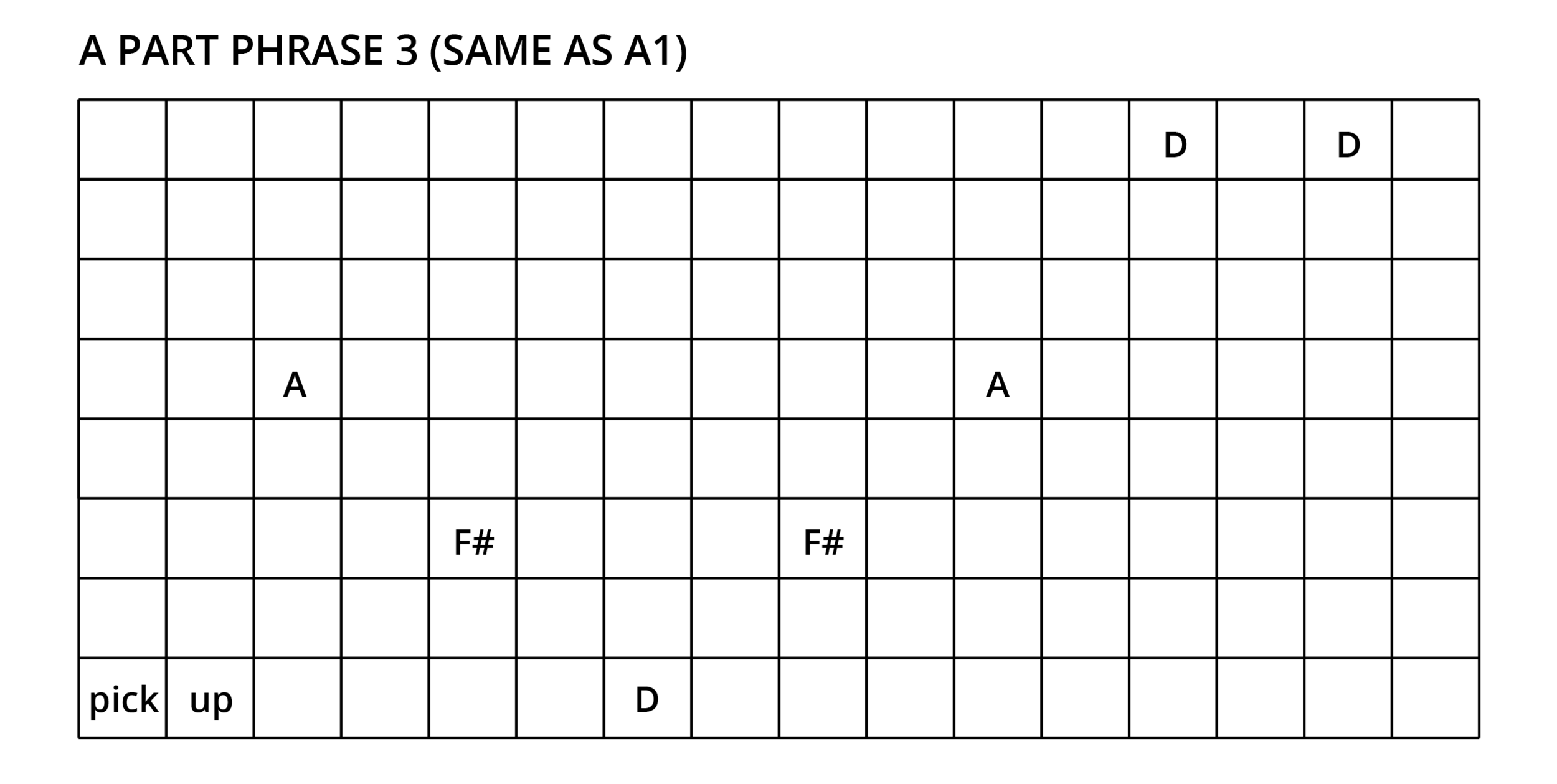

Here are six combinations for an A part phrase.

(The first three phrases of the A part start with the same bones).

In the first set, I’m considering the 1 to be F#, in the second set, the D is 1.

3213 3213 = AGF#A F#EDF#

3123 3123 = AF#GA F#DEF#

3213 3123 = AGF#A F#DEF#

3123 3213 = AF#GA F#EDF#

3213 1231 = AGF#A DEF#D

3123 1321 = AF#GA DF#ED

In this audio track I played through the first three phrases of the A part and left the fourth phrase empty, so you could practice your own choice. I repeated the A part so I could demonstrate all six combinations of the permutations I listed here.

Toggles

Adding an open string (that works with the chord progression) between each melody note can contribute quite a bit of sound and an element of frenzy. Sometimes it’s a nice effect! Other times it can be a little too Extra. You’ll have to use your judgement.

Double Stops + Chords

Adding another note above or below your melody can provide another texture AND more harmonic information. This is definitely my go-to for creating my own variations. I wax poetically (if I do say so myself) in this book, which helps you find chords all over your instrument, and I go on and on about how important knowing/understanding/hearing/playing progressions are to your musicianship and ability to jam or create in my curriculum. Thank you for checking out my lessons and books, and sharing these posts- your support directly impacts the life of this blog!

Here are two examples of adding simple double stops:

Change Octaves

Play an entire section in a different range! If the B part is usually higher than the A part, try playing the B part low. Or maybe bump one phrase to a different register? This is a fun and relatively safe and easy way to ‘improvise’.

Play with Rhythm

Running eighth notes (constant sound!) can be challenging and exhausting for both the player and the audience. Varying your rhythm is interesting for everyone. Try alternating between playing the bones (quarter notes + half notes) for one phrase, playing eighth note variations (arpeggios, passing tones, permutations, toggles) for the second phrase, back to bones, etc.

Another ‘trick’ for changing your rhythm is removing a few of the things you’ve added. Try this with the passing tones exercise. Here’s the example from before as a reminder:

You could remove all the G passing tones but keep the E passing tones. Or vice versa. Or play the G descending and the E ascending. Or vice versa. Here’s audio of me playing those 4 ideas: notice what it does to the rhythm.

Ornament the Ends of Phrases

If the ends of your phrases have space built into them, it’s often nice to add a grace note, turn, rock up or double stop.

And since I just talked about the ENDS of phrases, I think it’s a tasteful segue to the end of this post. Which is really just the BEGINNING of your improvising practice for the day/rest of your life. Good luck. Choose not to be overwhelmed. Instead, be inspired! Start small and gradually add more options for your decision-making prowess. You’ve got this. Let me know how it’s going. You can reach me through [email protected]

Be well,

xoL

*If you’re wondering how the flat seven chord functions in Mixolydian and minor tunes, this book will be your best friend.